loading map - please wait...

The Los Padres National Forest is a gem of true California wilderness, though it is often overshadowed by other recreational areas like Big Sur, the Sierras and the Mojave Desert. In the early days of California, it offered essential routes, hunting grounds, and homesteading for Spanish immigrants and Western pioneers; and for thousands of years prior, it was home to the native Chumash, Salinan, and Esselen people. Today, this forest protects some the most incredible rock art of ancient California peoples and unique and endangered animal species, such as the California Condor and the Arroyo Toad.

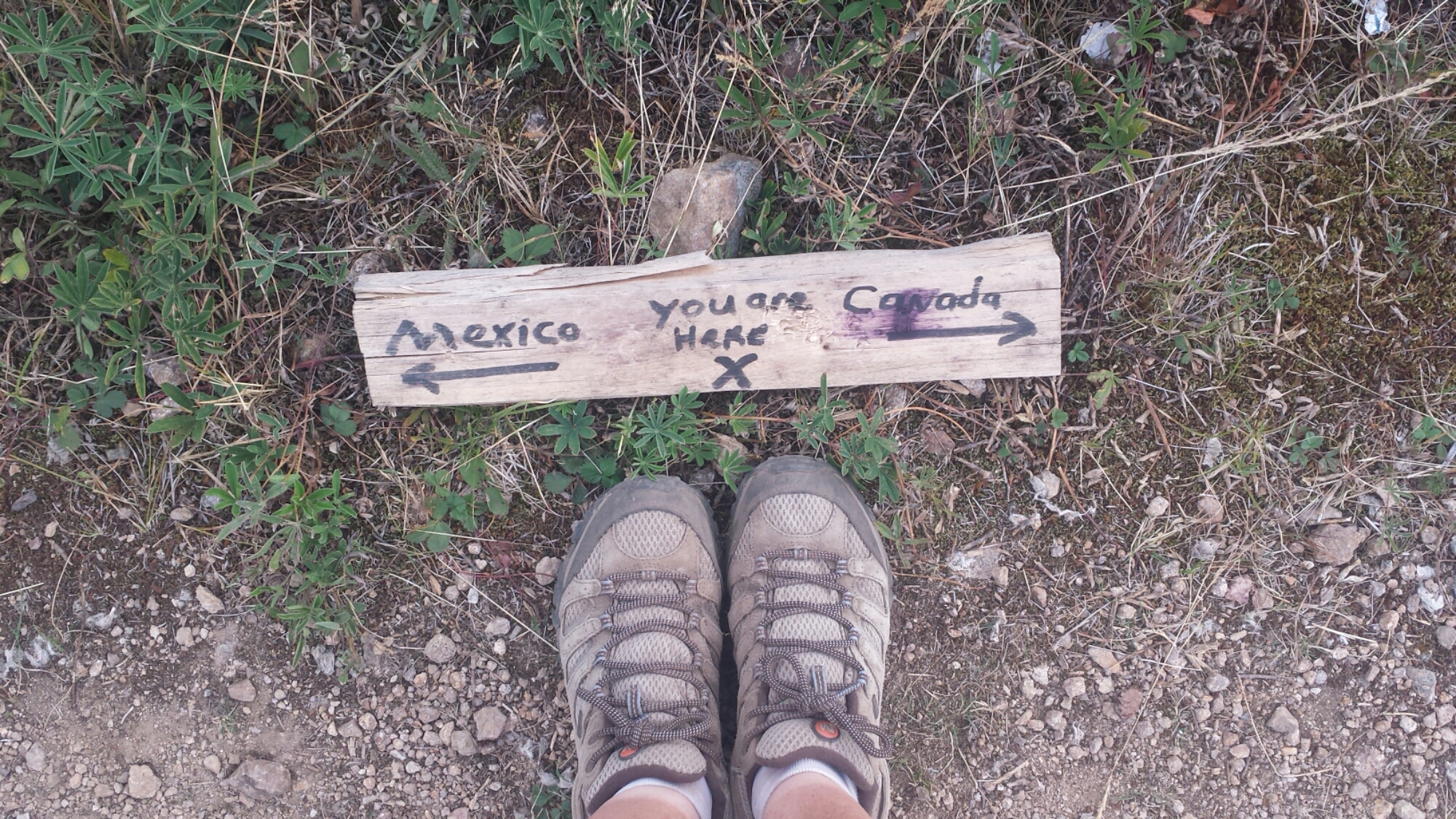

Though I have lived as its neighbor for my entire life, I’ve ventured into the depths of the Los Padres only a few times and never on my own. I’ve been intimidated by reports of difficult trail, if any was to be found, and feared the scenery would not be rewarding enough for the effort to see it. How could it possibly compare to all the beauty I experienced on the Pacific Crest Trail over the last two and a half years and why would I want to bother with bushwhacking when there are easier trails to hike?

I swallowed my doubts and decided to give this forest a chance. This trip took me on a 43-mile loop around Hurricane Deck in the San Rafael Wilderness, through some of the most scenic land and rugged trail; it opened my eyes to a different kind of adventure: a beautifully savage one and it nearly broke my heart.

Day 1- 2.6 miles to Fish Camp

After a four day skiing and hiking vacation in Shaver Lake with Art and our Queensland Heeler, Pepper, I came home exhausted, but ready for some time on the trail. Art stayed home to work on his paintings, while I headed out late in the afternoon with trepidation and excitement. I don’t usually bring our dog with me out of concern for her well-being, but I decided that because I wouldn’t be logging lots of miles every day, this would be a good trip to bring her on.

We headed out from Nira Campground along the Manzana Trail at 5:30 in the afternoon. The weather was perfect, the trail was clear, and all the Spring Break campers seemed to be sticking near their cars. The trail follows Manzana Creek along the western side of Hurricane Deck, a large Miocene sandstone formation that separates the Sisquoc River from Manzana Creek. It’s considered to be a very short mountain range, but being a single sandstone formation, Hurricane Deck can also be viewed as a very large mountain.

This area of California can be exceptionally hot in the summer time and the creeks are often dry from around June through November, with little water during the months of December and January. That being said, the ideal time to explore the Los Padres is in the Spring, when the creeks are full, the hills are green and the famous wildflowers of the area are in full bloom.

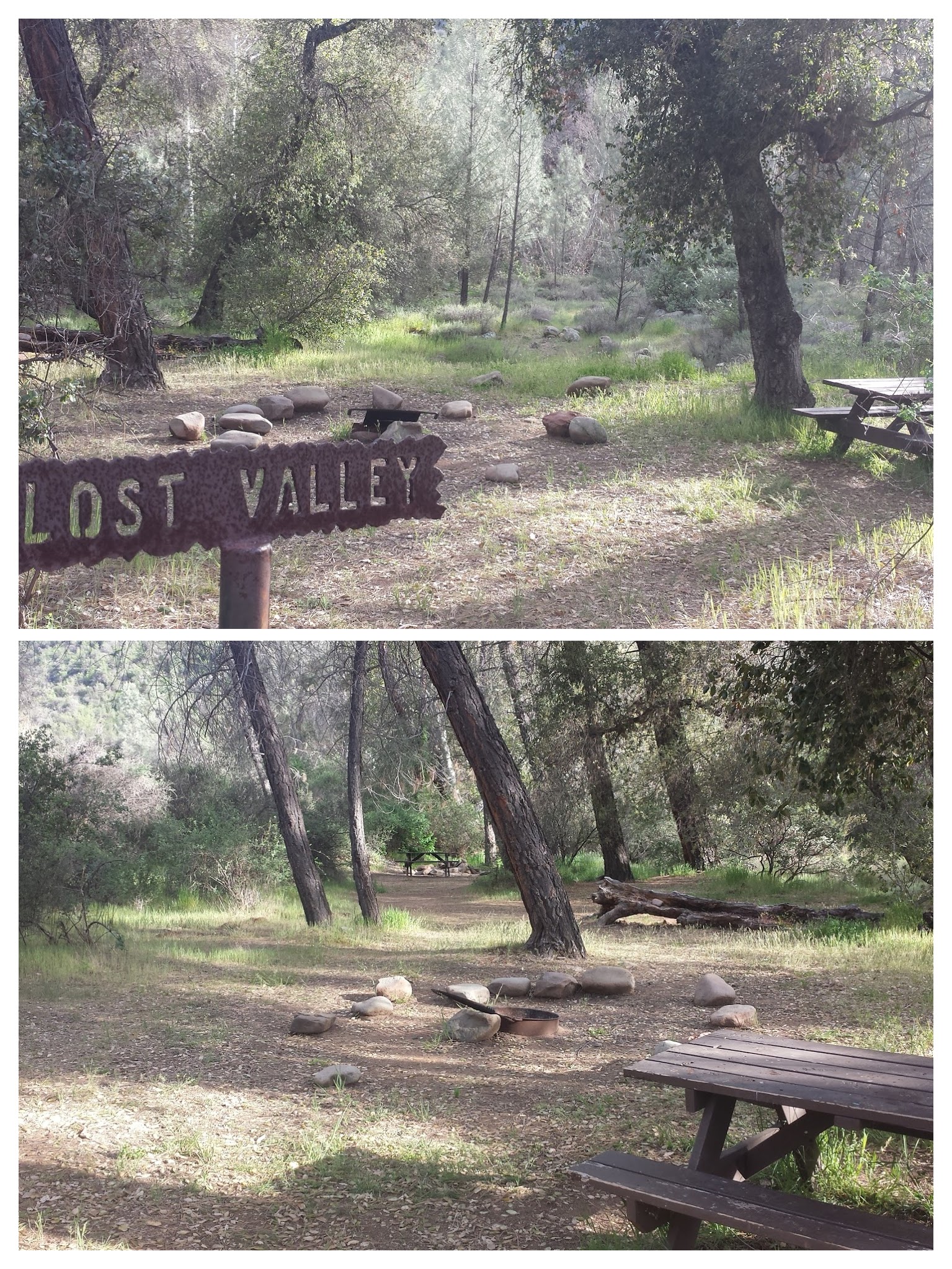

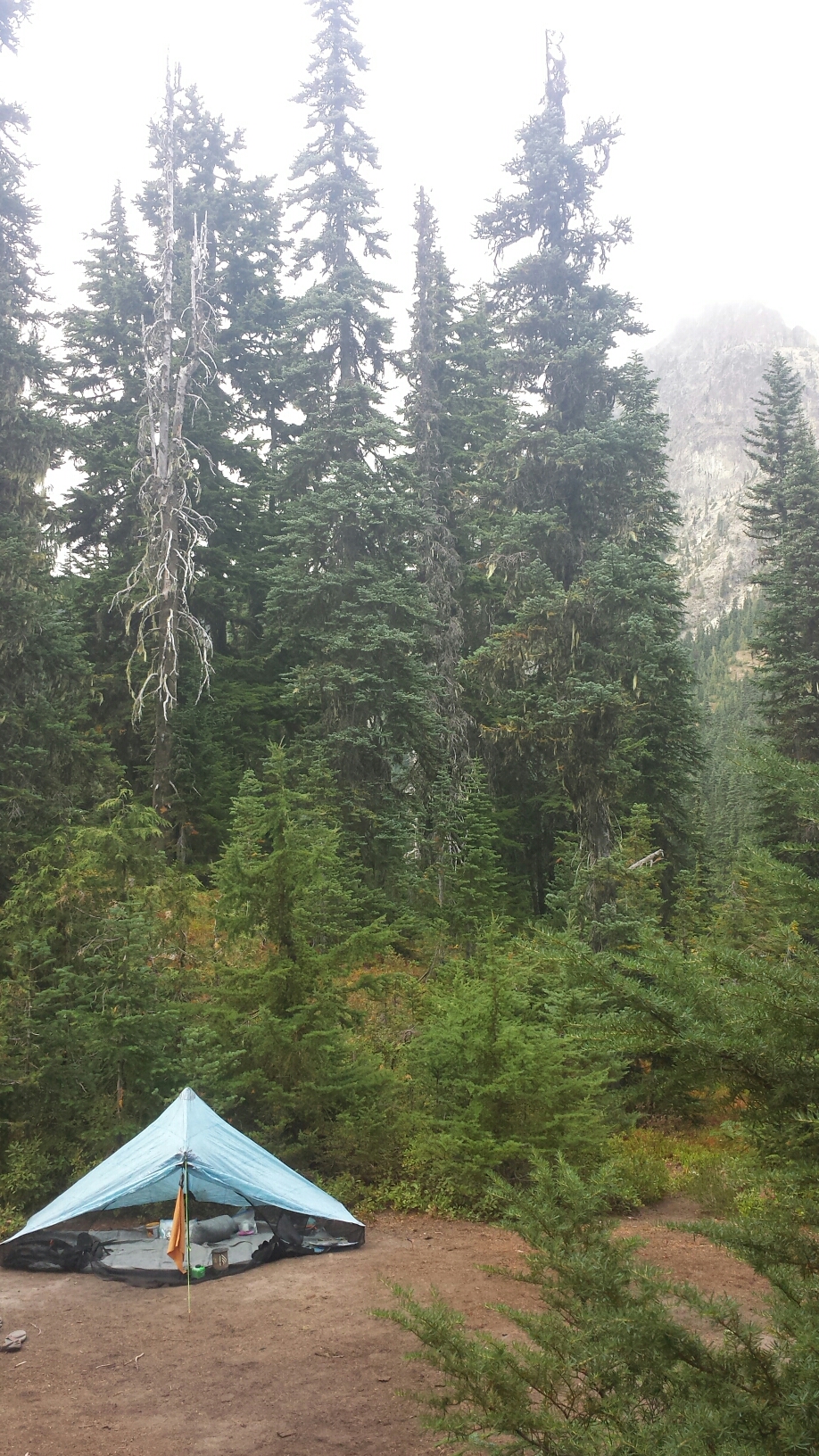

Unlike most of the camps I visited along the Pacific Crest Trail, the Los Padres campsites almost always have picnic tables, fire pits and thrones. (Thrones are exposed outdoor toilets, sometimes with a single wall for privacy.) Though it may not feel as wild having a table and toilet at your service, it offers a safe place to build fires in this tinder-box of a forest and a nice respite from the struggles of route-finding during the day.

We stopped at Fish Camp for the night, with not a soul nearby. There was water in the creek and the valley opened up around the camp allowing the last rays of sunshine to grace us. Although she’s gone camping before, Pepper really isn’t used to sleeping outside. The openness and exposure seems to freak her out- maybe it’s because she lives in an apartment with me and Art or maybe it’s because she was traumatized as a pup living as a stray.

Even if she’s been exposed to poison oak, I’ll keep Pepper inside the tent with me at night; I just give her a dirt bath first. Tonight she sat upright, on high alert, trying hard to peer through the bug netting of the tent, which was held up by safety pins because the zipper wore out after 2,600 on the PCT. I finally just pulled her inside the sleeping bag with me and cuddled her until we both fell asleep, my arm numb under the weight of her.

Day 2- 12.8 miles to South Fork Station

All day, the trail was easy to follow- no climbing over downed trees or pushing through thick bushes. I was absolutely delighted! The map I use was created by local cartographer Bryan Conant and he indicates clear trail with a yellow line and rugged to no trail with a purple line. The entire Manzana Trail is yellow- whoohoo!

The California wildflowers lived up to their reputation with popping colors of red, yellow, orange, purple and soft blues and whites. The Purplehead wildflowers, I learned, were an important part of the native American diet. Their starchy corms, or bulbs, are enjoyed by not only humans, but also bears, mule deers, rabbits, pigs, and gophers. Once the bulb is dug up, it aerates the soil and aids in controlling the plant population.

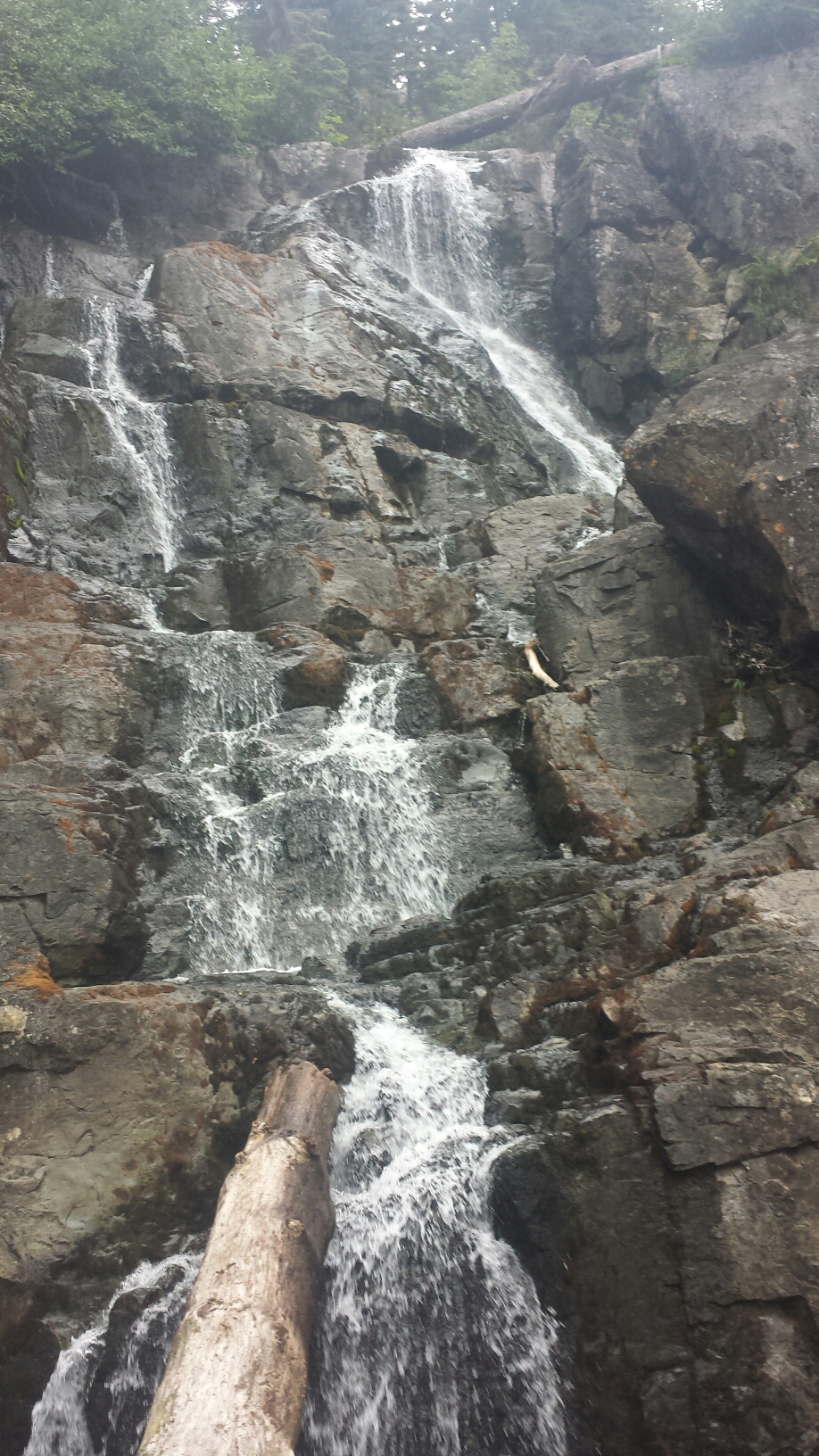

It didn’t take us long to reach the popular Manzana Narrows Camp. This site, sandwiched between sandstone canyon walls, is large enough for scout troops or school groups and is situated directly next to a swimming hole decorated with two beaming waterfalls. It’s here that I learned Pepper is a ratter. Normally trotting safely behind me, she went straight for a juicy rat eating leftover camp food and, to my surprise, my docile, city-dog caught it! She dropped the screaming rat as soon as I barked at her, but I think she was feeling pretty proud of herself. The rat seemed shaken up, but unharmed and dashed away through the dead oak leaves.

The Manzana trail soon leaves the cool, shade of the creek and switchbacks up to the stunning White Ledge Canyon. This high canyon is one of the most spectacular areas of the Los Padres, with sandstone formations protruding from the grassy earth and pine trees growing in the crevasses between them. If I had more time, I would’ve explored these rocks in the hopes of finding a secret cave or sacred artwork, perhaps dating back 10,000 or more years. As it was, I remained on the trail, stopping frequently to eyeball the rock walls and caves for any signs of artwork. The exact locations of known rock art are kept secret to protect them from vandalism.

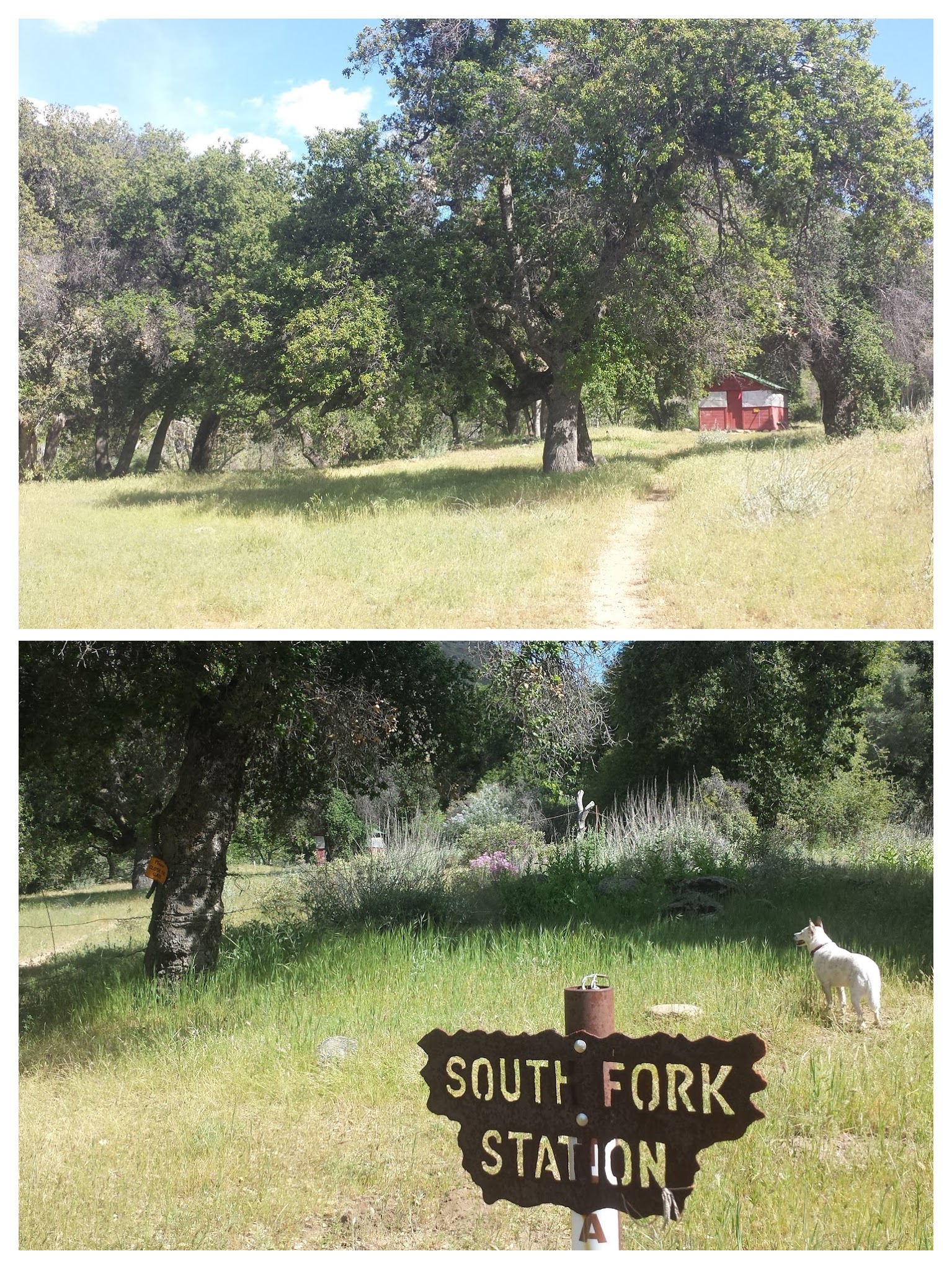

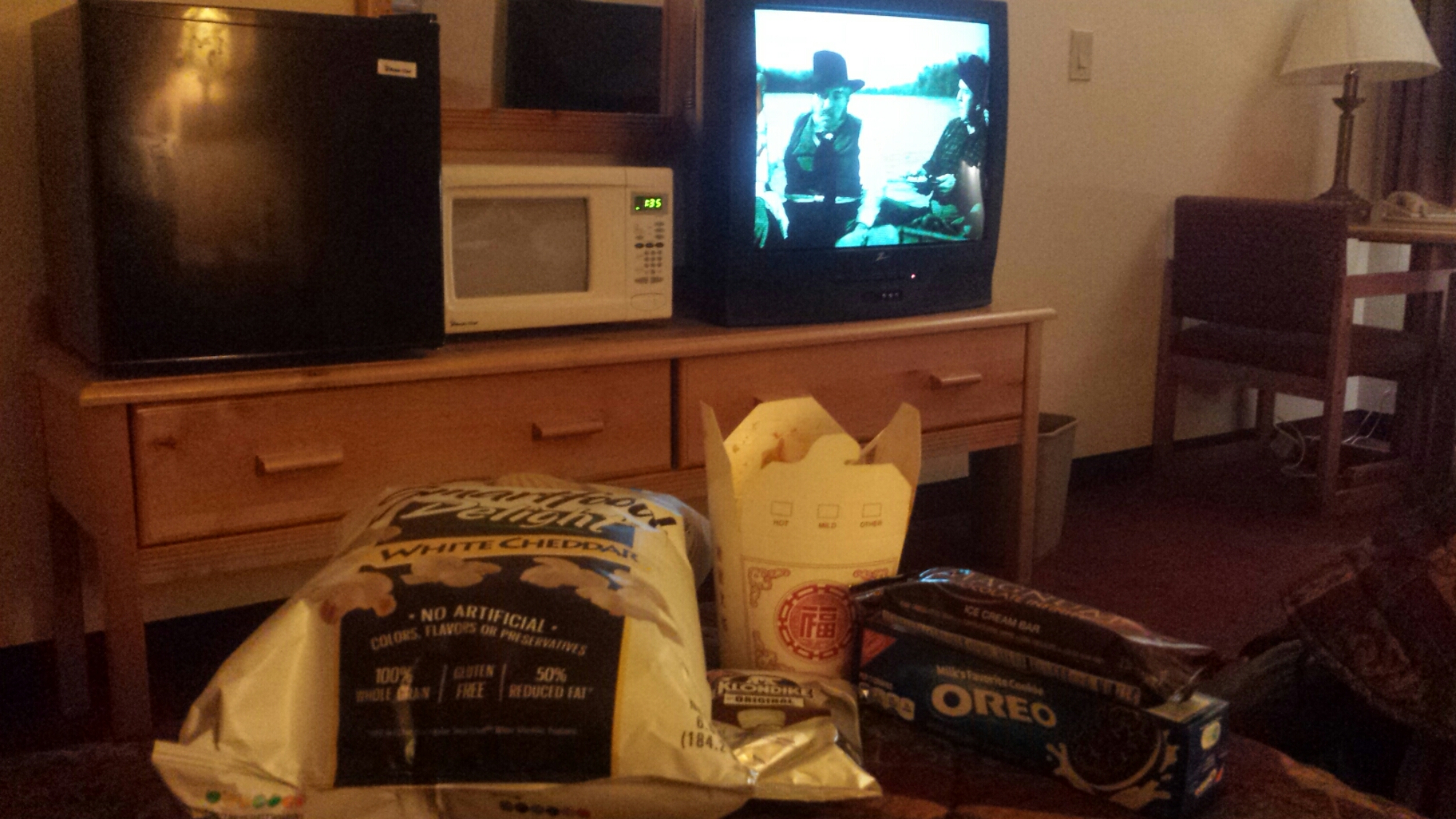

Pepper & I arrived at the South Fork Ranger Station around 3pm and helped ourselves to relaxing in the cool and bug-free cabin. The cabin is primarily used by the Volunteer Wilderness Rangers who maintain the trails, but they leave it unlocked for hikers to enjoy as well. The cabin is furnished with two cots, a wood-burning stove, and a tiny table complete with a red-checkered tablecloth. The shutters opened from the outside allowing generous light in, while screens kept the flies out.

After relaxing for about an hour, I secured the shutters and packed up my gear, ready to move onward, but Pepper made it very clear that she wasn’t interested in hiking. She just stared at me, even as I walked away from the cabin and made ready to leave through the gate. The 12.8 miles we’d hiked so far are the furthest she’s ever hiked in her little, doggie life and she was worn out. I had originally planned on hiking a southern loop along the Sisquoc, but it would require us putting in 15 miles each day. Knowing that this may be too much for Pepper, I had a back-up itinerary of 10-miles per day around the northern Sisquoc loop and decided to make a final call once we reached South Fork. Well, this was it, she was saying “No, way!” to 15 miles and we settled in at the cabin for the night. There was a tennis ball on the shelf and she didn’t seem too tired to play catch while I enjoyed a homemade dinner!

Day 3- 11.8 miles to Miller Canyon

I knew that today would be a more difficult hike, given that Bryan’s maps showed the Sisquoc River Trail as purple, and not the friendly shade of yellow; but no purple line on a map ever prepares you for the harsh reality of bushwhacking through jungle-like riparian woodland and thick grasslands. The morning began with a clear-enough path and beautiful views of sandstone-layered hills. Slowly and before my eyes, the land transformed from lush, green that had surrounded Manzana Creek and the South Fork Sisquoc, to dense river vegetation cutting through tall desert hills.

As the canyon around the Sisquoc narrowed, the trail transformed from overgrown grass to crumbling rock, clinging to the canyon sides. Eventually, the canyon opened up to form the Sisquoc River Valley, once home to about twenty homesteads housing two hundred religious settlers during the late 1800’s. Lead by fellow settler Hiram Preserved Wheat (1822-1903), these spiritual people believed in the power of faith healing and healing through the “laying-on of hands.”

The remains of these settlers can still be seen today: fragments of rock chimneys and rusted farm equipment have sat quietly for over 100 years in the grasses above the river. The settlers raised livestock, which they would drive into town via a wagon road through the Sisquoc Valley, and had gardens and orchards of grapes, apples, melons, beans and potatoes. As rain became more scarce over the years and access to the only road connecting them to town was denied by a local ranch, the settlers were forced to sell their prospects and relocate. For more fascinating information on these settlers, check out E. R. Blakey’s book, A Historical Overview of the Los Padres, or Jame’s Wapotich’s Blogpost, Trail Quest: Sisquoc River, Part 2.

I learned quickly that the Sisquoc River Valley has a pattern: the river wraps around brief stretches of grassland, which gives way to rocky cliffs as the river changes direction, forcing the trail to cross the river and climb up to the next grassland on the opposite side. Following the trail requires spotting a cairn or piece of faded red flagging on the opposite side of the river and then following the path of grass that’s about a foot shorter than the surrounding grass. At times, I just walked along the sandy riverbed or directly in the river itself because I couldn’t find where the trail picked up or because I simply couldn’t stand the foxtails getting stuck in my shoes any longer. Next time, I’m wearing my heavy-duty REI gaiters. Oh, yeah, and I’m bringing my bug net for the incessant flies!

There’s a saying I’ve heard, “If you’re not crawling on your hands and knees, you’re not in the Los Padres.” It definitely seemed to be true today. Every time the trail dropped back down to cross the river, I became tangled and caught in thickets of young willows and alder trees, pillowed by tall grass and deep mud. It was like navigating a maze of vines, wooden cages and quicksand, and I was Tarzan.

At times the river or the mud was too deep for Pepper and I would scoop her up and haul her across. More than once, I fell ass-first and Pepper face-first into the water. Normally a very quiet dog, she’d make a surprised and displeased grunt every time we took a tumble- she quickly learned to not squirm whenever we went through this process. Otherwise, she became very good at finding her own ways- drier ways- of crossing the Sisquoc.

Since Miller Canyon Base Camp was completely overgrown, though a beautiful site, I decided to hike onwards in search of a friendlier campsite. We found it at the very next river crossing. Pepper plopped herself down in the shade next to the river as I cleared a space on the bank above for our tent. I spent the evening playing in the water, while Pepper took anther dirt bath, and enjoyed the last rays of sunshine in the quiet air of the valley. I watched Pepper try to sniff crane flies and butterflies as they bounced through the air around her head. It was sweet and beautiful to watch and I felt perfectly at home.

Day 4- 17 miles to Nira Campground

There were many times yesterday when I was fed up with the trail. I was angry at the sharp, painful foxtails that stuck to me as I hiked through overgrown grass, frustrated with the seemingly impenetrable riverside foliage that forced me to crawl, stumble backwards into mud, or whacked me with a face-full of dusty leaves and absolutely beside myself when I’d look upon the opposite canyon wall to see a clear trail that I just couldn’t reach. This lasted for hours until I realized that the Los Padres required me to seriously adjust my attitude.

It was time to slow down, to enjoy the route-finding and rich details that can be discovered at this careful pace. I learned that a hike of 11-12 miles in the Los Padres backcountry was something to be very, VERY proud of at the end of the day. This realization hit me like a single, soft bell chime- I’ve been hiking the Pacific Crest Trail for two years in a row, which is practically a walk in the park compared to exploration of this remote land.

Pepper seemed to be doing better this morning than the previous two days- she was energetic and brave, bounding ahead through bushes and crossing the river without any encouragement from me. When we first adopted Pepper, she was very shy and absolutely terrified of wide, open spaces. Just taking her on a walk was an ordeal- she’d freeze and look around for signs of danger. Only bite-sized pieces of hot dog seemed enticing enough to shed her fear and moved forward through the big, scary world.

These days, Pepper is a bright, friendly pup who could walk herself to the park down the street if we let her. She’s the most naturally obedient and docile dog I’ve ever owned; she’s so submissive, she even tries to roll underneath our neighbors’ terriers and chihuahuas. Today, I became careless in my responsibility to her. It was so delightful watching her bravely want to lead the hike that I forgot about the danger it put her in.

Shortly after the above picture was taken, around noon, Pepper walked directly into a full grown rattlesnake and it bit before it could even rattle a warning. Being ten or so feet behind, I could hear the snake as I watched her immediately and confusedly u-turn back toward me. My initial thought was, “Good dog, you know not to check it out, good dog!” And then I saw her hind leg curled up as she limped closer to me. She attempted to walk a few more feet before she collapsed like a block into the sandy riverbed and then pulled herself with her three working paws into the shade of a boulder.

I rolled Pepper onto her back and looked frantically for a bite mark, and there it was: two small puncture wounds directly in her heel, small drops of blood already showing. Twenty-five percent of the time rattlesnakes do not inject their venom, but I wasn’t about to sit around to watch her suffer just to find out how much poison this snake had delivered. I don’t have any children- so all my maternal instincts have gone straight into this wonderful dog who has been our companion and side-kick for years. Without a second thought, I pulled out half my gear, lifted Pepper, hind legs first, into my backpack, and hoisted her 40 pound body onto my back. Placing her wound below her heart would help slow the poison disseminating in her small system.

We didn’t trek long before we ran into another rattlesnake, stretched under the shade of a manzanita bush. I felt my anger well up immediately, but rather than waste time hating on the random animal, I skirted around it until I came to a wall of crumbling rock that was apparently the trail. Even if I didn’t have Pepper on my back, it would’ve been a struggle to climb up it, so I detoured back toward the now aggravated snake and down a gully into the riverbed. Some kind of wildlife alarm must have gone off, because not five minutes of walking along the riverbed, we ran into a small black bear. He was meandering along the sand and turned, startled to look at us. The bear dashed ahead, but continued in the same direction as us along the river. Three times, the bear dashed ahead along the river before he figured out that I wasn’t going to change course and he finally turned up the riverbank and disappeared into the alders and grass.

I carried Pepper for five miles before we reached a clear trail at the Manzana Schoolhouse Camp. Exhausted and concerned about dehydrating or injuring myself, I stopped to rest before continuing along the Manzana Trail toward Nira Campground. I set the backpack with Pepper inside carefully on the ground and gently pulled her out to exam the wound. Her hind leg was now swollen and black with oozing blood. Rattlesnake venom prevents blood from clotting and causes blood vessels to leak like a wet sponge; victims eventually die from heart failure. I reached for my water bottle in the side pocket of my pack only to find I’d lost it somehow. Frustration, anger, and fear of loosing my loving dog now overwhelmed me and I finally let out a desperate scream. Once out, I couldn’t stop it, I screamed and I cried and screamed again. The water was no big deal; I could drink directly from Manzana Creek and worry about giardia later, but I did not want to loose my dog. All I could think was, “She’s too good to die like this!”

At that moment, two hikers heading toward the schoolhouse cabin, came around the bend and eased my nerves. They gave me a spare water bottle and helped me situate Pepper on my back again. I hiked onward, my shoulders and hips aching from the weight of her and my mind frantically analyzing the situation, “What’s my pace? Am I hiking fast enough to save her life? Will I get to the car before dark? … Headlamp’s in the side pocket; spare battery’s in the top pocket. … I’ll have reception on the road near the shooting range- should I call the vet first or Art? … There’s a packet of almond butter in your pocket- eat it so you have energy to hike faster.”

After another two miles, I stopped at a fork in the trail, confused about which branch to take, and a family of four emerged from a side trail. Amy and Dean, along with their two kids, Eric and Emma, were out for a day hike and they immediately offered to help carry Pepper the remaining six miles to my car. I couldn’t believe my luck. In that moment, I was so grateful I had to suck in my sobs because I didn’t want to unnerve them. Dean carried Pepper like a marine. He hiked so fast that the rest of us struggled to keep up. With his and Amy’s help, Pepper was packed securely in the front seat of my car and we were on our way to a vet before sunset.

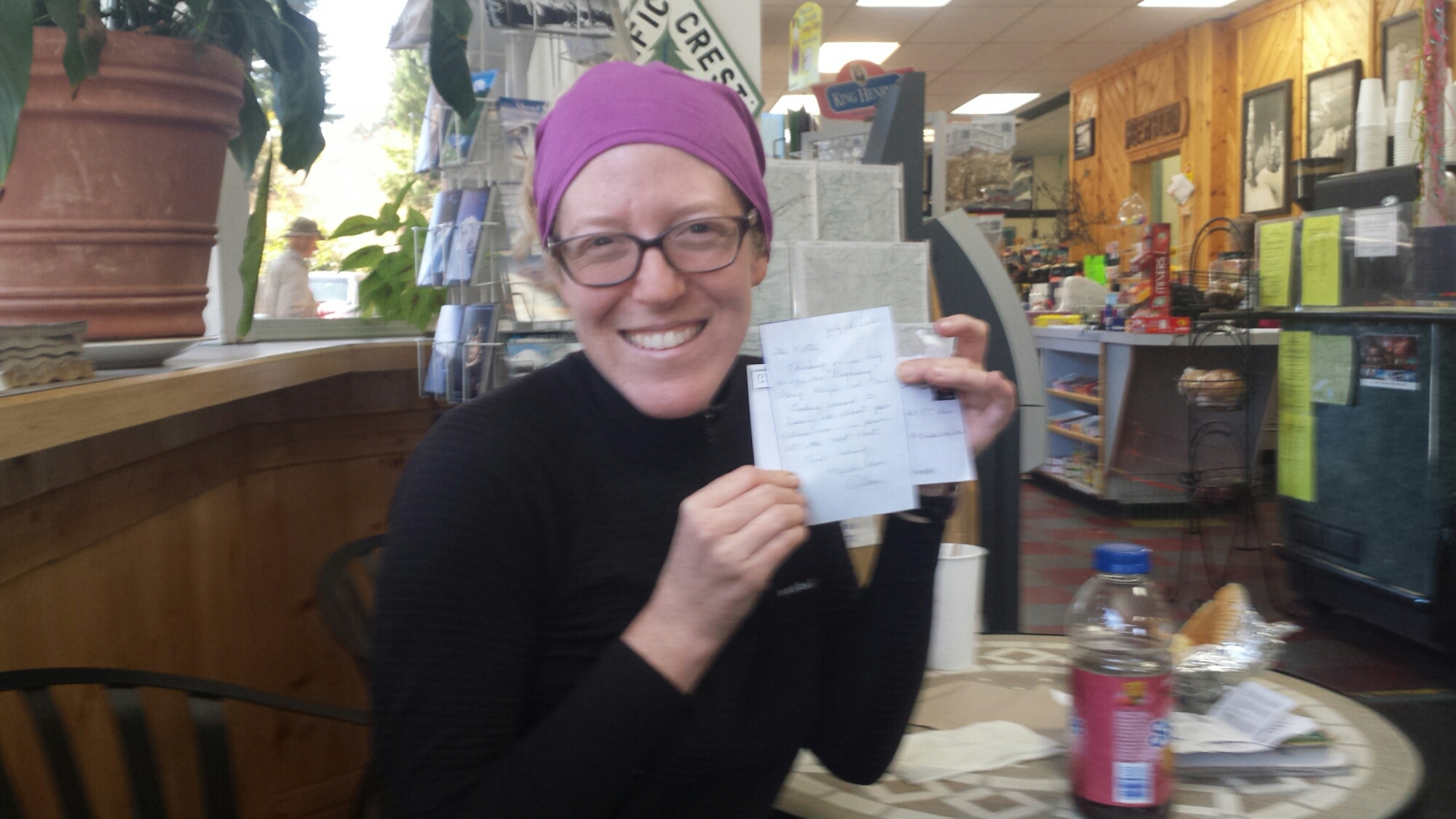

The Follow-up

Pepper received the finest medical treatment a dog could get for three full days and has pulled through to fight another one. She will continue to need medical attention from our regular vet for the next two to three weeks as we monitor the damage done to her blood and attempt to save the tissue around the bite on her leg.

I have learned a lot since she was bit. I was careless and irresponsible, and even though it was for a short time, it nearly cost her her life. While hiking the PCT, I was often teased for being overly cautious when it came to safety on the trail and I’ve now seen first hand how ugly and heart breaking it can be when hikers become lax with safety. Before taking Pepper on a hiking trip again, I will participate in a training program which will teach her to smell, recognize and avoid rattlesnakes and am considering giving her the rattlesnake vaccine, both of which I never knew existed until now. While she usually hikes behind me when I ask her to, I’ll be more proactive about keeping her there and not allowing her to trail blaze in front. Even on a leash, she would’ve reached the snake before me and still been bitten, so the most important things I can do now are train and vaccinate her.

Art has made several points to alleviate my guilt. First, this accident could’ve happened along any of the front country trails or open spaces that she and I hike weekly. It’s true that I’ve seen more snakes in the Santa Barbara front country than I have anywhere else while hiking. The difference is that accessibility to help in the front country is much higher than deeper in the mountains. Also, if I had been walking in front, the snake could have easily struck me instead and though I’ve carried a SPOT device with S.O.S. messaging for over two years, I didn’t have it with me on this trip. I canceled my membership because I didn’t think I’d need it this year. If I had been bitten, I would’ve had no way of requesting help and the chances of being found by another hiker in that remote area are miniscule. That dog may have just saved MY LIFE. Words cannot express how grateful Art and I are for the help of Amy and Dean and the expertise of the veterinarians- without them, I may not be sitting here now with Pepper safely at home.

Links- Snake Safety

Training your Dog to Recognize & Avoid Snakes- Youtube Video

Snake Safety Information from the Forest Service